Do I still need to take the ACT or SAT?

Three years into the COVID-19 pandemic, a lot of policy and confusion remains around how colleges evaluate standardized test scores. Many universities adopted a test-optional policy during the pandemic, and some schools will retain that position permanently. Many colleges, however, are reinstating standardized test requirements for applicants. So how do you know which guidelines to follow?

First of all, check the current policies of any school to which you might submit an application. Do this by consulting the school’s official Admissions Department website or by speaking with someone in that office. These policies may change application cycle to application cycle, so make sure any information you reference is current.

Most students apply to a mix of schools, some of which require scores and some of which do not, so it is very likely that all students who are in high school now will need to take a standardized test.

Schools with Testing Requirements

If a college or university requires a standardized test score with the application, students must submit a valid test score. Again, many schools that permitted students to opt-out of this submission during the pandemic are reinstating this requirement, so it is essential that you read application requirements very carefully.

For a list of some colleges requiring test scores, click here. Note that these will continue to change year-to-year.

Test-Optional Schools

Test-optional schools do not require students to submit standardized test scores but will accept them and use them to evaluate an applicant. If students choose not to submit test scores, admissions officers will focus on other parts of the application. Most importantly, these schools do not penalize students who cannot or do not submit test scores; however, strong test scores can boost students’ applications.

As a rule, students should submit scores to test-optional schools when their scores are at or above the school’s 75th percentile for average scores. However, for more information on whether or not to submit scores, see my 2021 blog post on this topic.

Note, however, that even when a school is test-optional, students may need to submit a test score to qualify for certain types of financial aid (more on this below).

Click here for a list of test-optional schools.

Test-Free Schools

Test-free schools (some schools still use the term test-blind) do not accept standardized test scores at all. This method removes entirely test scores as a metric for admissions; all applicants are evaluated on GPA, extracurriculars, essays, etc.

Some Test-Free Schools (for 2023-24): University of California system, University of Minnesota, Reed College, Boise State, North Carolina Wesleyan. For more click here.

Financial Aid Based on Test Scores

Standardized test scores can be a deciding factor in many types of aid offers. Applicants for National Merit Scholarships, for instance, must submit a standardized test score. Some universities offer automatic scholarships to any student achieving certain GPA and test score requirements, and so submitting test scores to these universities is essential in order to be considered for this type of aid.

Here are a few examples of schools that offer automatic aid when students meet specific GPA and test score requirements:

West Virginia University offers in-state students $4,000 of aid with a 1390 SAT or 31 ACT, plus a 3.4 GPA. Out-of-state students receive $16,000 worth of aid for the same scores/GPA.

The University of Tennessee offers in-state students $9,000 of aid with a 1490 SAT or 34 ACT, plus a 3.8 GPA. Out-of-state students receive $18,000 for the same scores/GPA.

The University of Kentucky offers automatic scholarships for both in-state and out-of-state students. Their Bluegrass Spirit Scholarship (out-of-state) provides $8,000 to $12,500 with a 3.00 GPA and 25 ACT/1200 SAT for $8,000, 3.50 GPA and 25 ACT/1200 SAT for $10,000, or 3.50 GPA and 30 ACT/1360 SAT for $12,500.

Is the ACT moving to a digital test?

In the months before the COVID-19 pandemic, ACT announced plans to offer an online test (see my 2019 blog post for more information) along with online, single-section retests. While ACT still has not rolled out single-section retakes (and won’t for some time), they have released a full Computer Based Test. While it seems that the computer-based version of the ACT may be the trend of the future, the transition to this format has been slow, and most tests are still being given in the original pencil and paper format.

The online version of the ACT is a Computer Based Test (or CBT). A Computer Based Test is simply an online version of the same test students take with pencil and paper. (A CBT is different from a Computer Adaptive Test (CAT), which adjusts the questions students see based on their performance in a prior section). The ACT’s CBT is identical in length, format, and question type as to the paper version, and the questions cover the same content.

Although ACT now has a functional computer based version, its use is currently limited. International students use the CBT exclusively, however, and no longer have the option of taking a paper test. Some US high schools are administering CBT tests on required school wide ACT test days. However, tests given on Saturday national testing days remain paper and pencil only; students who register for the ACT as individuals are not given the option of taking the ACT CBT.

If you are curious about the ACT CBT, ACT offers a practice CBT online at ACT.org, although students must create an account to access the sample. As mentioned above, the question formats and instructions are identical to a paper copy of the test. During administration of a CBT, students will receive either scratch paper or a whiteboard to use for figuring out answers to math questions. As with the written test, these materials are provided by the school or testing site and collected at the end of the test. The ACT CBT offers students helpful onscreen tools including a highlighter function, the ability to mark and review questions from anywhere in a test section, and others.

It is reasonable to assume that eventually ACT will migrate to using the CBT more frequently, if not exclusively. However, this has been slow, and a full format conversion will not likely happen quickly. Right now, ACT prep looks very similar for students taking either test, but those who know they will be taking the CBT should at a minimum familiarize themselves with the online test tools to maximize their performance on that test.

COVID-19, Test-Optional Policies, and You

When the COVID-19 Pandemic caused a nationwide shut-down in March, 2020, no one anticipated the complications that would arise as businesses closed and workplaces, schools, and other essential services moved online for over a year. The pandemic’s effects on the world of standardized testing have been severe and far-reaching. Because of building closures and social distancing restrictions, many 2020 tests were completely cancelled. Those that occurred did so on a limited basis. These drastic changes made taking a test impossible for many high school students in 2020/early 2021 and, in some places, tests are still not being offered.

Colleges and universities recognized the difficulties students were having scheduling tests and also the inequities caused by students’ varying access to tests. Therefore, most colleges and universities became either test-blind or test-optional for 2021 applicants. Many of these policies have been extended through 2022, and some schools made the changes permanent.

So…when test scores are optional, how do you know if you should submit them if you have them?

Below is some information to help you navigate the terminology and the strategies for deciding whether or not you should submit your standardized test scores when you apply to college.

Test-blind vs. Test-optional

Universities and colleges took two approaches toward test scores during the pandemic. Some schools (for instance, the entire University of California system) decided to become test-blind schools. Test-blind schools do not accept standardized test scores at all. Even if a student submits them, the school will not evaluate or consider them. This method removes entirely test scores as a metric for admissions; all applicants are evaluated on GPA, extracurriculars, essays, etc.

Test-optional schools do not require students to submit standardized test scores but will accept them and use them to evaluate an applicant. These schools do not penalize students who cannot or do not submit test scores; however, strong test scores can boost students’ applications. Though some schools were test-optional pre-pandemic, and some colleges have become test-optional on a permanent basis, most colleges and universities adopted this policy only temporarily (through 2021 or 2022). For example, all 17 colleges in the UNC System will remain test-optional through 2022.

You must carefully check the official Admissions Department website of schools to which you apply to find each one’s current policy on test scores.

Should I submit my test scores?

If you were able to take a standardized test and you have an official score, how should you decide whether or not to send it with your college applications? When students have spent so much time and money preparing for and taking these tests, it can be difficult to analyze this question objectively. It can seem wasteful to not use your score. However, I encourage students and parents to take a step back and make this decision based on facts alone. The answer depends on three main variables: the competitiveness of the school to which you are applying; the average test score for the school to which you are applying; and the strength of your test score relative to your GPA.

It is extremely important to note that if you are applying to test-optional schools and choose not to submit a test score, colleges will not automatically assume that you took a test and had a low score. There are many reasons applicants do not have test scores this year; tests were cancelled all over the country, many tests that operated had limited seats, financial constraints on families made testing a large obstacle for many, and the list goes on. Colleges and universities with test-optional policies will not penalize you or make assumptions about your application if you do not submit scores.

How does my test score compare to other applicants’?

Almost every college that accepts test scores will advertise the average scores of its most recently admitted class of students. Most Admission Department websites display an “Admitted Student Profile” that outlines the demographics of the school’s incoming freshman class. This information includes geographical data, gender and race breakdowns, and average test scores of admitted students. The college will usually provide a range of test scores that represent students from the 25th percentile through the 75th percentile of the admitted class. This is called the “Middle 50,” and it gives applicants a great way to judge whether or not their test scores will be considered weak or strong.

If your test scores fall below the given range, or if they are on the low end of the range, you should likely not submit them. Again, you will not be penalized for not submitting test scores. But you may be penalized for submitting a test score that is below average. Submitting a low test score will only hurt you.

If, however, your score is 75th percentile or higher, I advise you to submit your score. In this instance, the score can only help you.

How does my test score compare to my GPA?

A solid test score can bolster a GPA that may not completely represent your abilities. If your GPA is not as high as you wish, or if you struggled with online learning and experienced a GPA dip, submitting a high test score will only help you.

On the flip side, if you have a high GPA but a test score on the lower end of the range, submitting a test score will likely hurt you.

If you have a high GPA and a high test score, submitting the test score won’t add much, but it certainly won’t hurt you and it will reinforce your strong application.

How competitive is the school to which I am applying?

If you are applying to a school that is highly competitive (20% or lower acceptance rate) and you have a high test score (at or above the school’s 75th percentile), you should probably submit your score. In a competitive environment, your score provides an additional data point for s school to use when considering whether or not you would be successful at the institution.

If your test scores fall below the given range, or if they are on the low end of the range, you should not submit them to a highly competitive school.

Note on Merit Scholarships:

Some schools use standardized test scores to evaluate students for merit-based scholarships and grants. If the school to which you are applying uses this as a metric and your score is high enough to warrant consideration, you will want to make sure to submit your score. Check the official website of your potential schools to see if they use test scores in this way.

The differences between test prep and academic tutoring, part I

Score improvement should be the primary goal of any test prep program. Students will certainly learn concepts and ideas along the way, but that learning must always prioritize points over concepts. This prioritization shapes fundamentally how I will approach a given concept with a student. For example, a recent ACT featured a question similar to the one below:

First, look at the question from a math-content perspective. The definition of a logarithm tells us that if x and b are positive real numbers and b does not equal 1,

logb(x)=y is equivalent to by=x.

Using this definition, we can use our understanding of negative exponents to solve by computing the following:

So E is the correct answer.

Next, let’s look at this question from a test-strategy perspective. Our primary goal here is to earn the point, not necessarily to understand the mathematical concept being tested. Under the MATH menu of the TI-84 Plus calculator is the logBASE option.

We can use that function to enter the log as given, plug the answer choices in for x, and check each answer choice until we find the answer that yields -3, which will still be E. In this case, the multiple-choice test format and the calculator have helped us bypass the actual math of the problem.

Which way is better if both approaches earn the point? The best way to do a problem is the way that occurs to a student in the moment of the test and the way that will yield a correct answer quickly. That approach will necessarily depend on the individual student and the individual question. Some students spend many hours drilling logarithm and exponent rules, thus the content approach provides an instant, easy point for this question. For most students, however, the strategy approach wins. If a student without prior understanding of logs and/or negative exponents takes the time to learn those rules, the return on his/her time invested is low because these concepts appear infrequently on the ACT. The same student can increase his/her calculator competency relatively quickly, so that student’s time will be better spent, and the return on investment of that time will be higher, by learning the functions of the calculator strategically.

There are many ACT questions that can only be solved through the application of specific content knowledge and many that can be solved through a less content-centered and more strategy-minded approach. The most prepared student can apply various strategies to various problems throughout the test to get the most total points.

The partial truth of “shortest answer wins” on ACT English and SAT Writing and Language

Both the SAT and the ACT contain a test of grammar rules. As any parent can attest, the days of diagramming sentences and learning parts of speech are gone, and many students confess that the only English grammar they know comes from what they learned in foreign-language classes and then applied to English.

Consequently, simple strategies like “always choose the shortest answer” appeal, since this strategy requires no specific grammatical knowledge and can be applied instantly. Both the SAT and the ACT prize conciseness and test it in a variety of ways. While it is fair to say that the short answer is often correct, it is not entirely accurate to say that it is always correct. Here is a typical example of the shortest answer as the correct one:

The Ballets Russes first performed the Rite of Spring on May 29, 1913 in Paris, in the twentieth century.

A. NO CHANGE

B. marking the first performance of this work.

C. in France.

D. DELETE the underlined portion and end the sentence with a period.

The correct answer is D, because answer choices A, B, and C all contain redundancies which make D the only grammatically correct answer. A student may or may not see these redundancies or may not understand that such redundancies are grammatical errors. As a result, a student who does not understand the grammatical issue but applies the general principle of shortest is best will still choose D and earn the point.

There are, however, times when the shortest answer will not be correct. If you are looking for a perfect or almost perfect English score, learn these exceptions to help you refine your strategy.

Clear pronoun use:

Both SAT and ACT test pronoun clarity, meaning a pronoun must always clearly refer to its “antecedent,” or what it replaces. For example, in the sentence “I tried to balance my coffee cup, my pencil case, and my daily planner, but I tripped and dropped it.”, the pronoun it can refer to the cup, case, or planner. To fix this sentence, it must be replaced by a specific item, which will necessarily make the sentence longer. Here’s what this question would look like in test format:

I tried to balance my coffee cup, my pencil case, and my daily planner, but I tripped and dropped it.

A. NO CHANGE

B. that.

C. the one.

D. the planner.

D is the correct answer here, even though it’s the longest.

Parallel construction:

Both SAT and ACT test parallel construction, which requires that phrases or clauses within a sentence follow the same format or structure. Consider the sentence “I prefer the books of JK Rowling to Ernest Hemingway.” The comparison intended here is one between books of one author and books of another author, yet what is actually compared here are JK Rowling’s books and Ernest Hemingway as a person. A correct version of this could be “I prefer the books of JK Rowling to those of Ernest Hemingway.” Here’s what this question would look like in test format:

I prefer the books of JK Rowling to Ernest Hemingway.

A. NO CHANGE

B. the books of Ernest Hemingway.

C. him.

D. those.

B is the correct answer here, even though it’s the longest.

“Shortest is best” is a powerful strategy, especially if a student is guessing at an answer. However, the examples above show that the strategy deserves a bit of refinement for those students who want the highest scores in English and Writing and Language.

ACT to offer computer-based testing and individual section retesting

ACT recently published a press release announcing the introduction of computer-based testing and individual section retesting. A link to the original press release is here, and a digest of the changes follows.

ACT’s press release offers the following information:

· Starting in September 2020, ACT will allow students who have already taken the ACT to retake individual sections without sitting for the entire exam.

· These individual section retakes will be offered only online (through school testing centers) and only to students who have previously taken then complete test.

· Cost is TBD.

· ACT will provide students who sit for these individual sections with a new superscore: a composite calculated using the highest four test sections taken from multiple test dates.

· Also starting in September 2020, students will be able to choose whether they want to take the complete ACT online or via paper and pencil. The online test will return scores in two days, rather than two weeks.

· The content and structure of the online test will be identical to those of the pencil-and-paper test.

While these changes definitely sound like good news for students, they also raise many questions that don’t have immediate answers. Chief among them is whether an ACT-computed superscore will change colleges’ test-reporting policies. As an example, University of South Carolina currently only superscores the SAT. According to its website, USC will only “consider the highest composite score from a single ACT test date.” (https://tinyurl.com/y3q5fay9, accessed 10/9/19). USC and other colleges have not yet assessed these new ACT single-section retests and schools are not obligated to accept the new superstores. If a school’s score reporting policy changes, students will then need to understand which application cycles the changes impact.

Additionally, the probability of a smooth September 2020 online debut seems small. ACT has been in the process of rolling out online testing for over five years, and testers on the vanguard of this change have faced multiple problems. Notably, when ACT moved all international testers to computer-based testing in 2018, many tests were cancelled in the week or two prior to the test date because test centers were inadequately equipped to handle the test’s technological and logistical challenges. The issue of test-center requirements also raises an important issue of access: will every student have the same access to the single-section retakes? If no, which students will receive priority?

ACT’s new testing options will also impact the landscape of ACT test prep. After taking the full test once, a student could conceivably prep for each section individually and then sit for only that single section. This could significantly help the student who struggles to stay focused for the duration of the full test or the student who hits his/her goal scores in three of the four test sections and only needs/wants to retest on that weakest section. In contrast, the opportunity to continually retest section by section seems to exacerbate the already protracted testing process. Clearly ACT’s new options promote increased testing, but this might not always benefit the test takers.

With the start date of September 2020, juniors and families of juniors might be tempted to plan for section retests just before fall early-decision/early-action deadlines. Given all of the current unknowns, this strategy seems risky. For now, students should stick to their original testing plans and assume that the new single-section testing option will not impact their applications. While students may be able to capitalize on a section retest opportunity, they should not rely on this option.

The Ins and Outs of SAT Subject Tests

Standardized testing doesn’t necessarily end with the general SAT or ACT. Many colleges include SAT subject tests in their recommendations or requirements, and, as a result, students should understand whether they will need to take these tests and, if so, which ones they should take.

College Board (maker of the general SAT test and AP exams) also makes SAT subject tests that focus on specific subjects including math, science (biology, chemistry, and physics), history (of the world and of the US), English Literature, and foreign languages. Each subject test takes one hour, and students can sit for multiple subject tests on a single testing day. The maximum score on each test is 800. For test dates and registration deadlines, visit https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat-subject-tests/register/test-dates-deadlines

Because requirements vary widely, the world of SAT subject tests gets confusing quickly. Some colleges require SAT subject tests with all applications. Some colleges “strongly recommend”, or “recommend”, or “consider” subject tests. Some colleges require SAT subject tests only if an applicant takes the general SAT and not the ACT. Additionally, colleges change requirements frequently, so students need to look at the admissions pages of their goal schools frequently for the most recent information. A Google search for “which colleges require SAT subject tests” offers many articles and lists with outdated information. Case in point: Cornell quite recently dropped its subject-test requirements, yet it still shows up in many lists as a school with subject-test requirements.

Students who need to take SAT subject tests should choose the test or tests that parallel their current coursework. For example, if a student takes AP World as a sophomore, s/he should take the World History subject test in the spring of his/her sophomore year while that knowledge is fresh. Note, however, that the AP exam and the subject test are not identical, so students should prep for the subject test separately.

As with the general SAT and ACT tests, a “good score” depends entirely upon the school and the specific program to which the student applies. Students should use two criteria when assessing subject-test scores: how they compare to their general SAT/ACT scores and how they compare to the scores of other applicants at that school. SAT subject tests can enhance a student’s application if those scores parallel or best his/her general SAT/ACT score. Most colleges with subject-test requirements already have high SAT/ACT requirements, thus students should aim for scores above 700 (or potentially above 750) to remain competitive with other applicants. If a college does not absolutely require subject tests (for instance, if it “recommends” or “considers” test scores, but does not require them), students should consider submitting subject-test scores only if they truly add to their applications. For SAT Subject test percentile ranks, visit https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/sat/pdf/sat-subject-tests-percentile-ranks.pdf

ISEE and SSAT: What's the difference?

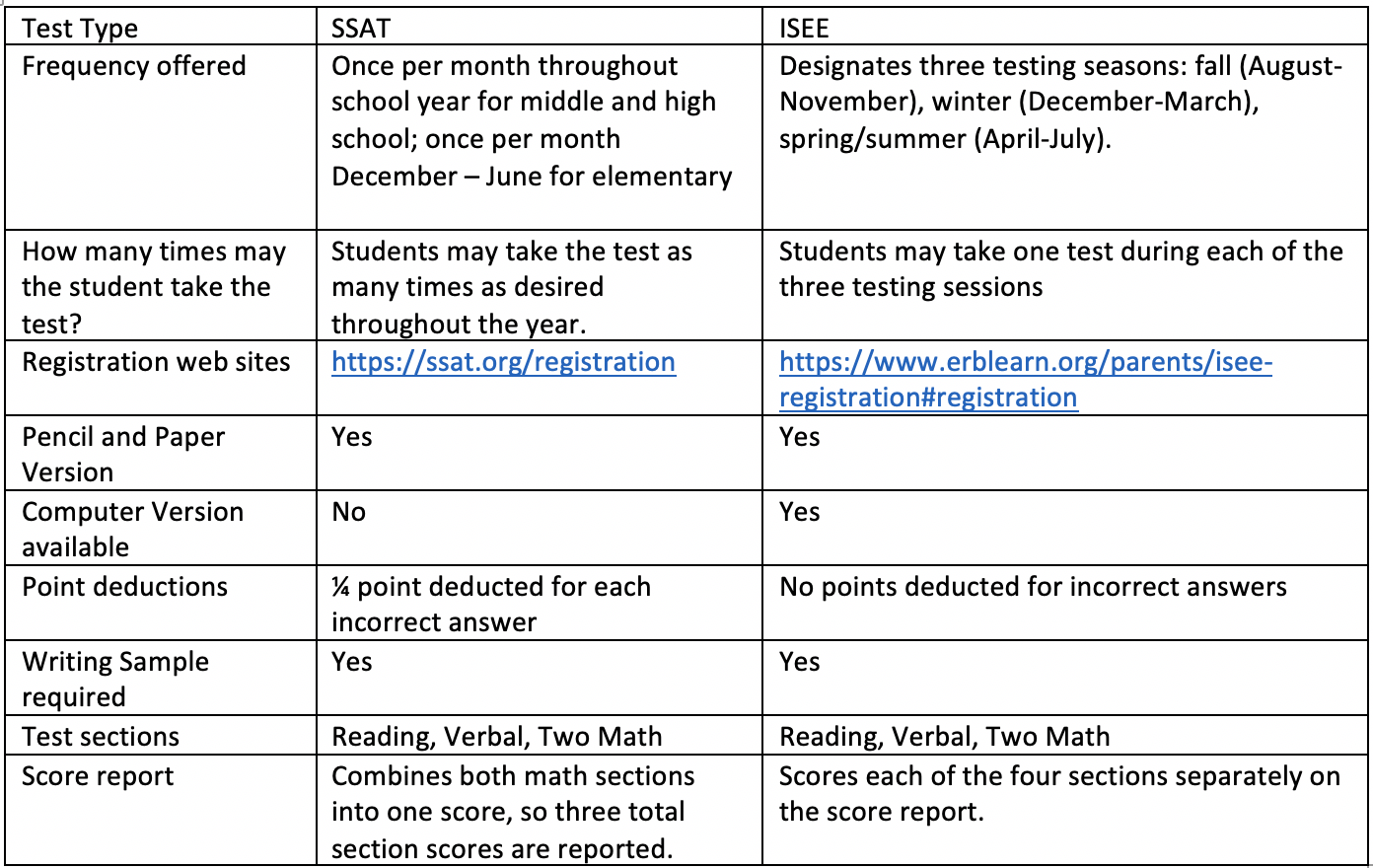

Students applying to a private elementary, middle, or high school typically need to take either the ISEE (Independent School Entrance Exam) or the SSAT (Secondary School Admissions Exam) as part of the application process. These tests are not simply mini SATs or ACTs: they are unique tests with some question formats that are not featured on college admission tests. Students benefit greatly both from choosing the best-fit test (if they are allowed a choice) and from thoughtful test prep.

Test Levels

SSAT Elementary Level: for application to grades 4-5

SSAT Middle Level: for application to grades 6-8

SSAT Upper Level: for application to grades 9-12

ISEE Primary Level: for application to grades 3-4

ISEE Lower Level: for application to grades 5-6

ISEE Middle Level: for application to grades 7-8

ISEE Upper Level: for application to grades 9-12

Test formats and frequencies

Within each test are various levels of material geared toward the entire block of test takers. Depending on his or her age, a student may see content that is two to four grade levels above what s/he currently studies. The scoring of each test compares the tester only to other testers in the same grade. For example, a student entering fourth grade will take the SSAT for 4-6 graders. Because the material on this test is geared toward a range of grade levels, the rising 4thgrader will see material that is two or more grade levels above his/hers. However, the student will be scored only in comparison to other rising 4th graders, not to rising 5th or 6th graders taking the same test.

Which one should you take?

If your student is applying to a school that accepts either test, it’s worth taking a practice test of each to see which might be a better fit. In addition to the differences noted above, each of these tests also have various characteristics that may be better suited to your student’s strengths. For example, the SSAT verbal section consists of only synonyms and analogies while the ISEE verbal section contains synonyms and sentence completions. While all of these question types test vocabulary, only sentence completions test vocabulary in context. The ability to use context clues in sentence completion questions can help a student who may struggle a bit more with vocabulary, which makes the ISEE verbal slightly more forgiving. In contrast, the math on the ISEE tends to be slightly harder than the math on the SSAT. Not only does the upper level ISEE test a few more advanced topics than does the SSAT, but the ISEE also provides less time per question which raises the test’s difficulty level.

Test frequency can also play a role in test choice. A student can take the SSAT more frequently than the ISEE, which can help families who are working with a compressed testing timeline. The ability to test more frequently can also help students who may have increased test anxiety and will benefit from taking multiple tests.

These tests can seem quite confusing due to the multiple test versions, timelines, question types, et cetera, but it’s worth doing some research into which tests your schools will accept and creating a testing timeline to set your child up for success.

Standardized test curves: The process of equating

People frequently ask me which test date or dates will have the best curve and will therefore give test-takers the greatest scoring advantage. In school, students often lament a well-prepared peer who “ruined the curve” of a particularly challenging classroom test, and most people assume that the same logic also applies to standardized tests. While standardized test scores are indeed adjusted, the process differs from traditional “curving.” Unlike school exams that a teacher might curve after s/he administers the test and evaluates student performance and score distribution, standardized tests are curved (a process called “equating”)before the administration of that test.

Standardized tests are so named because schools can compare student results across years, providing a consistent scale for student evaluation. For each test, a student receives a raw score (total number of correct answers) and a scaled score (raw score adjusted to a predetermined scale). While the raw to scaled score conversion can vary slightly with each test, the overall distribution of scores will be the same. Standardized tests are engineered and scaled such that the score distribution fits a bell curve: most students will score close to the average (the middle part of the curve) and very few will do extremely well or extremely poorly. (You do not, in fact, get 200 points on the SAT just for putting your name on the test, but if you get even a single question right anywhere in the test, you are likely to earn at least that many points.) Equating takes into account the difficulty of the questions and anticipates student performance to insure that, regardless of difficulty, test scores will maintain the same distribution.

The way in which a test is equated can still affect your score. For example, the June 2018 SAT received widespread complaints (google “June 2018 SAT curve” if you like) as high scoring students felt their math scores were lower than they should have been. On this particular test, if a student missed two math questions, s/he received a score of 750. On previous tests, two missed math questions would have resulted in a 790 or 780. What’s the difference? The difficulty level of the test. The math on the June 2018 SAT was too easy—it did not contain enough hard elements and thus the equating of this test was extreme. As a result, many students saw their accuracy increase on this test while their scaled score actually decreased. Arguably College Board should have better engineered the June 2018, but given that the test was easier than normal, it stands to reason that each error would have a greater impact.

What does all of this mean for you and your student? First, you always want a hard test! The more difficult the material, the better the curve, so each mistake becomes less significant, particularly at the top of the scale. Second, plan to take multiple official tests to make the most of these slight differences. At the top of the scoring scales, the difference between a 33 and a 34 or a 1550 and a 1570 can be a single question. Third, start your prep and testing early so that you have room in your schedule to add an additional test if needed.

Understanding the equating process is just one more step toward reaching your goal score. By taking multiple official tests and understanding that the degree of difficulty will vary between tests, you can leverage your own content strengths and test-taking skills to achieve your personal best.

Differences Between the PSAT and SAT

Our last blog post addressed differences between the PreACT and the ACT. Today we will examine the relationship between the PSAT and SAT as it is fundamentally different that that between the PreACT and ACT.

There are a few versions of the PSAT that students will take at various points during middle school and high school. Eighth and ninth graders take the PSAT 8/9. A variety of talent search programs, including Duke Talent Identification Program (https://tip.duke.edu), use these scores to evaluate student eligibility. Tenth graders take the PSAT 10. Note that while some scholarship programs use this score in their searches, the National Merit Scholarship Program does not. Tenth and eleventh graders take the PSAT/NMSQT. The National Merit Scholarship Program uses this version of the PSAT to evaluate student eligibility. For the purposes of this comparison, I am using the PSAT/NMSQT.

Format of the PSAT/NMSQT

Reading: 47 questions, 60 minutes (1min16sec/question)

Writing and Language: 44 questions, 35 minutes (48 sec/question)

Math Test – No Calculator: 17 questions, 25 minutes (1min28sec/question)

Math Test – Calculator active: 31 questions, 45 minutes (1min27sec/question)

Format of the SAT

Reading: 52 questions, 65 minutes (1min15sec/question)

Writing and Language: 44 questions, 35 minutes (48sec/question)

Math Test—No Calculator: 20 questions, 25 minutes (1min/15sec/question)

Math Test—Calculator Active: 38 questions, 55 minutes (1min27sec/question)

The PSAT/NMSQT is scored on a scale of 1520 total points. This total score breaks down into two subsections, Math and Verbal, each scored on a scale of 760.

The SAT is scored on a scale of 1600 total points. This total score breaks down into two subsections, Math and Verbal, each scored on a scale of 800.

The PSAT’s slightly lower score range accounts for the lower difficulty level and shortened nature of this test. While the Writing and Language sections are identical in question number and length, the other three sections are extended on the SAT. The Calculator Inactive math section changes the most from PSAT to SAT as the SAT eliminates almost fifteen seconds per question. This particular section poses unique obstacles to students who rely on a calculator for basic math computation.

Although the scales of the two tests are not identical, a student’s PSAT score directly equates to his/her predicted SAT score. For example, if a student scores a 1250 on the PSAT, s/he should score a 1250 on the SAT as well. Additionally, the PSAT allows students to identify strengths and weaknesses within each subject that can help in SAT preparation. However, students should take a full-length practice SAT before beginning any SAT prep program, as this is the most accurate way to assess students’ SAT test-taking skills.

Differences Between the PreACT and the ACT

I always ask students to take a full-length practice ACT before beginning any test prep package. This approach may appear redundant when students already have detailed score reports from their PreACT tests. Success on the PreACT, however, does not always correlate to success on the ACT. Understanding the difference between these tests along with their respective benefits and limitations is vital to student success with the prep process. (Information regarding the relationship between the PreSAT and the SAT will be discussed in an upcoming blog post.)

The PreACT is intended for high school sophomores, although any high school student can take it. Schools decide if and when to administer the test and inform students and families of the test date and registration process. The school will administer the test during a regular school day. If you have any questions about the testing timeline at your child’s school, reach out to a counselor.

Because the PreACT is targeted to sophomores instead of juniors, it is somewhat easier than the ACT. Students receive a PreACT score (out of 35) as well as a predicted composite score range and predicted section score ranges for the ACT (out of 36). Unlike the ACT, the PreACT has no essay section. The PreACT provides an important introduction to the format and demands of the ACT. The detailed score report helps students identify general strengths and weaknesses that the student can then work on before taking the ACT. The included predicted range of ACT scores provides a rough guideline, but does not always predict accurately ACT success.

PreACT

English: 45 questions, 30 min (40 seconds per question)

Math: 36 questions, 40 min (67 seconds per question)

Reading: 25 questions, 30 min (72 seconds per question)

Science: 30 questions, 30 min (60 seconds per question)

--no essay--

ACT

English: 75 questions, 45 min (36 seconds per question)

Math: 60 questions, 60 min (60 seconds per question)

Reading: 40 questions, 35 min (52.5 seconds per question)

Science: 40 questions, 35 min (52.5 seconds per question)

--optional essay section--

In the above breakdown, note the shorter allocation of time per question across all sections, particularly in reading and science. Students who finish these sections without issue on the PreACT are often surprised to find that they run out of time on those same sections of the ACT. Additionally, the increase in total test time from 2 hrs 10 min to 2 hrs 55 min (longer if the student opts to write the essay) increases fatigue as well as the likelihood of mistakes.

While the PreACT certainly provides a helpful preview of college admissions testing, a full-length practice ACT predicts more precisely performance on the ACT. The full-length practice test also helps the tutor more accurately assess issues with pacing across all sections which then allows the student to cultivate better pacing strategies from the start.